There are moments in medicine when the language itself changes. When words like “treatment” and “response” quietly give way to heavier phrases: “no remaining options,” “palliative focus,” “making the most of time.” For families facing aggressive blood cancers, especially those that strike children and teenagers, that shift can feel abrupt and devastating. It is the point at which science appears to have reached its limits.

Yet in hospitals across London, a small group of clinicians and scientists have been refusing to accept that limit as final. Their work has culminated in a highly experimental gene-edited immune therapy that is not curing cancer outright, but doing something just as meaningful for some patients: reopening doors that had firmly closed.

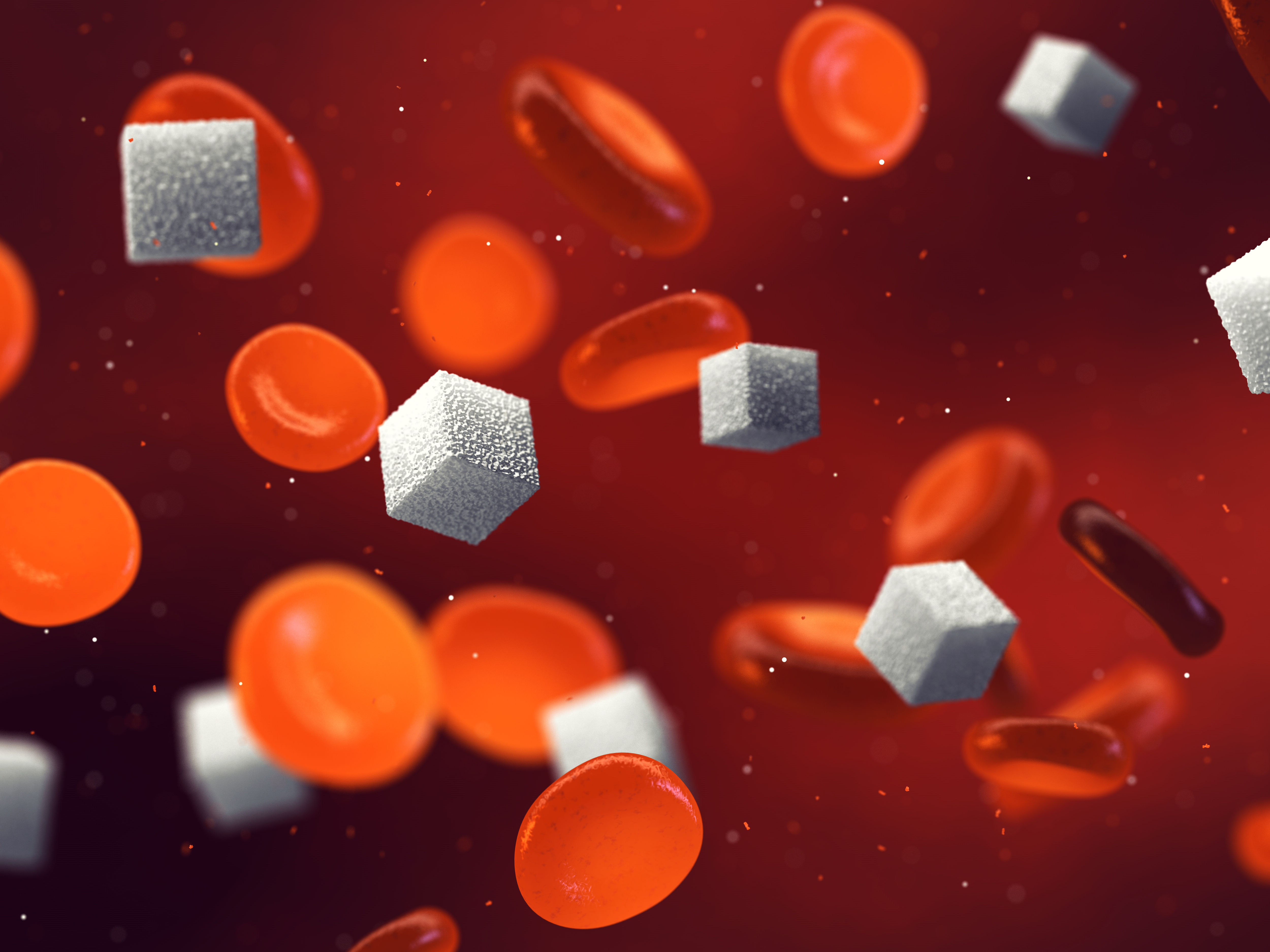

The therapy, known as BE-CAR7, has now shown encouraging results in an early clinical trial involving children and adults with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, a rare and fast-moving blood cancer. Published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the study suggests that precise gene editing can turn donor immune cells into a temporary but powerful weapon against a disease long considered one of the hardest to treat.

This is not a story about a miracle cure. It is a story about persistence, precision, and what happens when cutting-edge science meets patients who are willing to take extraordinary risks when there is little left to lose.

A Disease That Moves Faster Than Medicine

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia, or T-ALL, is uncommon, but when it appears, it does not wait politely. Originating in T-cells white blood cells essential for immune defence the disease spreads rapidly through the blood and bone marrow. Patients can become critically unwell within weeks, suffering infections, bleeding, severe fatigue, and organ complications as healthy blood cells are crowded out.

Modern treatment protocols are aggressive by necessity. Children and adults with T-ALL typically endure months of high-dose chemotherapy, often followed by a stem cell or bone marrow transplant designed to rebuild a healthy immune system. Many patients respond well, and survival rates have improved dramatically over the past generation.

But for a significant minority, estimated at around 20 percent, the disease either fails to respond or returns after initial treatment. When relapse happens, it often happens quickly and violently. Options narrow, time compresses, and families are forced into decisions no one should have to make.

For these patients, T-ALL is not simply difficult to treat. It is often unforgiving.

Why T-Cell Cancers Defied Immunotherapy

The past decade has seen immunotherapy revolutionise cancer care. CAR T-cell therapies, which involve genetically modifying immune cells to hunt down cancer, have transformed outcomes for certain lymphomas and B-cell leukaemias. In some cases, patients with advanced disease have gone into long-term remission after a single infusion.

Yet those same successes only highlighted a glaring absence. T-cell cancers remained stubbornly resistant to similar approaches.

The reason lies in biology. CAR T-cell therapies rely on T-cells as both the weapon and the target. When the cancer itself is a T-cell, the strategy risks collapsing in on itself. Engineered cells can attack one another, destroy healthy immune cells indiscriminately, or be eliminated by the patient’s immune system before they have a chance to work.

For years, this problem was considered one of the final frontiers of cellular therapy. The idea of instructing T-cells to selectively kill malignant T-cells without triggering immune chaos seemed, to many, unattainable. BE-CAR7 exists because researchers refused to accept that assumption.

Rewriting Immune Cells With Surgical Precision

At the heart of BE-CAR7 is a gene-editing technology known as base editing. While often mentioned alongside CRISPR, base editing is distinct in an important way. Rather than cutting DNA strands, it allows scientists to change individual DNA letters directly, reducing the risk of unintended genetic damage.

Using this approach, researchers take healthy T-cells from volunteer donors and subject them to a series of precise edits. These edits remove receptors that would normally cause donor cells to be rejected by a patient’s immune system. They also eliminate markers that would cause engineered T-cells to recognise and destroy one another.

Finally, the cells are equipped with a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR, that allows them to identify a specific marker found on T-ALL cancer cells. The result is a highly specialised immune cell, programmed to seek and destroy malignant T-cells while temporarily sparing the patient from immune collapse.

What makes this approach especially significant is that the cells are universal. Because they are derived from donors and extensively edited, they do not need to be custom-built for each patient. They can be manufactured in advance, stored, and delivered when needed a critical advantage when treating fast-moving cancers where weeks can mean the difference between life and death.

The First Patient and an Untested Idea

The world’s attention first turned to BE-CAR7 through the experience of a teenage girl from Leicester. Diagnosed with T-ALL after months of unexplained illness, she underwent standard treatments, including chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant. None succeeded.

As her condition deteriorated, her medical team began discussing palliative care. It was at this point that researchers at Great Ormond Street Hospital and University College London offered something unprecedented: an experimental therapy that had never before been used in a human being.

Agreeing to the treatment meant stepping into the unknown. The risks were immense. The therapy required wiping out her remaining immune system, leaving her vulnerable to infection. There were no guarantees, no long-term safety data, and no precedent to fall back on.

She agreed.

The treatment process was gruelling. Weeks in isolation followed, with careful monitoring for dangerous immune reactions. But the engineered cells did what they were designed to do. They cleared the cancer to levels undetectable by the most sensitive tests.

Years later, she remains cancer-free. Her case did not just save a life; it provided proof that an idea once considered too dangerous or complex might actually work.

Expanding Hope Beyond a Single Case

One success, however remarkable, does not define a therapy. Recognising this, researchers expanded their work into a formal phase 1 clinical trial, enrolling additional children and adults whose T-ALL had stopped responding to conventional treatment.

The participants represented some of the most difficult cases clinicians encounter: patients for whom the usual pathways had failed and whose prognoses were bleak. For many, participation in the trial was not a hopeful gamble but a final option.

The results, now published in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggest the initial success was not an anomaly. Most participants reached deep remission after receiving BE-CAR7, allowing them to proceed to a stem cell transplant. For several, remission has persisted for years.

Just as importantly, the trial offered insights into how the therapy behaves inside the body. Researchers tracked how long the engineered cells persisted, how the immune system rebuilt itself, and why some cancers were able to adapt and return. These lessons will shape future iterations of the therapy and inform how it might be combined with other treatments.

The Cost of Pushing the Frontier

It would be misleading to describe BE-CAR7 as gentle. This is among the most intense treatments modern medicine can offer.

Patients undergoing the therapy temporarily lose their immune defences entirely. Infections that would be trivial for a healthy person can become life-threatening. Long hospital stays, isolation, and constant monitoring are unavoidable. Some participants experienced severe complications, and not all survived.

In a small number of cases, the cancer found a way to evade the therapy by shedding the marker the engineered cells were designed to recognise. These relapses underscore an uncomfortable truth of cancer biology: it adapts.

Researchers are candid about these risks. BE-CAR7 is not intended to replace existing treatments or be used early in the disease course. It is designed for specific, high-risk situations where the alternative may be no treatment at all.

Life After the Headlines Fade

For patients who respond and move on to a successful transplant, the journey does not end with remission.

Recovery from a bone marrow transplant can take months or years. Fatigue, vulnerability to infection, and medication side effects often persist long after hospital discharge. Some survivors face chronic complications that require lifelong follow-up.

Children and teenagers must navigate disrupted education, social isolation, and the psychological impact of prolonged illness during formative years. Families, too, carry the emotional weight of uncertainty long after the immediate crisis has passed.

In this context, BE-CAR7 is not a cure in the conventional sense. It is a bridge one that allows patients to reach a point where longer-term recovery is possible.

A Glimpse of Medicine’s Next Chapter

Beyond its immediate impact on T-ALL, BE-CAR7 offers a glimpse into the future of cancer treatment. The concept of off-the-shelf, gene-edited immune cells challenges the idea that advanced therapies must always be bespoke, slow, and prohibitively expensive.

If refined and scaled, similar approaches could be adapted for other rare cancers and conditions where speed is critical. Researchers are already exploring whether base editing could help overcome resistance in other malignancies long considered beyond the reach of immunotherapy.

Significant obstacles remain. Manufacturing complexity, cost, regulatory oversight, and equitable access all pose formidable challenges. But the success of BE-CAR7 demonstrates what is possible when scientific ambition is matched with sustained investment and collaboration.

The Human Element Behind the Science

It is easy to focus on gene edits and remission rates, but none of this progress would exist without people willing to take extraordinary risks. Patients and families agreed to experimental treatments at moments of profound vulnerability, often knowing the outcome was uncertain.

Clinicians and researchers spent years refining techniques that might never have reached the clinic. Charitable organisations, public funders, and volunteer donors supported work that offered little guarantee of success but immense potential impact.

These human choices to participate, to persist, to invest are as much a part of the breakthrough as the technology itself.

Holding Realism and Hope Together

BE-CAR7 does not herald the end of cancer, nor does it erase the suffering associated with aggressive disease. What it does is quieter, and perhaps more important.

It extends the boundary of what is possible. It offers an option where none existed. It turns the phrase “nothing more we can do” into something less final.

For patients and families standing at the edge of that conversation, even a small shift can change everything. And for medicine as a whole, BE-CAR7 is a reminder that progress often arrives not as a cure, but as an opening one more chance to keep going.