What if the journey to Mars didn’t take six grueling months, but just over a month? No more drifting endlessly through space, no more radiation-soaked, bone-thinning stretches of isolation. Just a smooth, high-speed ride across the solar system—like a cosmic express train.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s the bold vision behind a cutting-edge propulsion technology that could change everything we thought we knew about space travel. Developed in the United States and tested on Earth, this new kind of rocket doesn’t rely on the brute force of traditional chemical engines. Instead, it uses something far more futuristic—and far more efficient.

The technology has been in development for decades, inching closer to a real-world breakthrough. If it delivers on its promises, it won’t just shorten the journey to Mars—it might just open the door to a new era of human exploration.

So, what exactly is this revolutionary engine? How does it work? And more importantly—can it truly live up to the hype?

The Problem with Traditional Rockets

For all the dazzling achievements of space exploration—moon landings, Mars rovers, and orbiting telescopes—there’s a sobering reality we often overlook: we’re still traveling through space using technology that hasn’t evolved much since the Cold War. Sure, the computers are smaller and the cockpits are more comfortable, but when it comes to propulsion, we’re still mostly lighting a giant candle and hanging on for the ride.

Traditional rockets, known as chemical rockets, work by igniting fuel and ejecting it at high speed to produce thrust. It’s dramatic, powerful, and loud—perfect for punching through Earth’s gravity. But that power comes at a cost. These rockets guzzle fuel at an astronomical rate, and most of that fuel is burned in just the first few minutes of flight. After escaping Earth’s pull, what’s left of the spacecraft essentially coasts toward its destination, making only minor course corrections along the way. That might be fine for satellite deployment or moon missions, but for deep space exploration? It’s the equivalent of revving your engine for a block and then hoping you can coast across the country.

Efficiency is another big problem. Chemical propulsion systems typically offer a “specific impulse” (a measure of efficiency) in the range of 300 to 450 seconds. That might sound like a lot—until you consider that the trip to Mars could take 6 to 9 months. During that time, astronauts face increased exposure to radiation, weakening muscles and bones due to microgravity, rising psychological stress, and a greater chance of system failures. It’s not just about getting there—it’s about getting there alive and functional.

To make matters worse, chemical rockets require staggering amounts of fuel—up to 90% of a spacecraft’s initial weight is fuel alone. That’s a logistical and economic nightmare, especially for missions where every kilogram counts and launch costs can be measured in millions.

It’s clear the current model isn’t sustainable for long-term, interplanetary travel. If humanity wants to explore Mars, settle the moons of Jupiter, or send robotic emissaries to the edges of the solar system in anything less than decades, we need a new kind of propulsion—something cleaner, smarter, and capable of sustained thrust over vast distances.

Enter VASIMR: The Plasma Rocket Revolution

Imagine a rocket engine that doesn’t roar like a dragon but hums like a microwave. One that doesn’t gulp down gallons of liquid fuel but sips on gas atoms superheated into plasma. That’s not a pitch for a sci-fi movie—it’s the concept behind VASIMR, the Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket. And if it lives up to its promise, it could upend everything we know about how to get from one planet to another.

VASIMR isn’t just a clever acronym—it’s the result of decades of research that bridges the gap between experimental physics and next-gen aerospace engineering. Born in the minds of MIT researchers in the 1980s and brought to life by former astronaut Dr. Franklin Chang-Díaz through his company Ad Astra Rocket, VASIMR has gone from lab bench to test rig with one bold goal: slash the time it takes to reach Mars.

Instead of relying on combustion like traditional rockets, VASIMR uses radio waves to convert a neutral gas—like argon, xenon, or hydrogen—into plasma, the fourth state of matter. This plasma is then manipulated using strong magnetic fields, accelerating it to blistering speeds and ejecting it to create thrust. The result is a system that’s quieter, more efficient, and remarkably versatile.

One of VASIMR’s game-changing features is its ability to vary its specific impulse—essentially letting engineers fine-tune the balance between speed and fuel efficiency in real time. Need to reach your destination faster? Crank up the power. Want to conserve fuel and coast more slowly? Dial it back. This kind of control just doesn’t exist with chemical rockets, which are essentially set on “burn or coast” mode.

Even more impressive is how VASIMR is designed for the long haul. With no internal parts physically touching the superheated plasma, there’s minimal wear and tear—making the engine incredibly durable. And unlike other ion engines, which tend to produce only tiny nudges of thrust over very long periods, VASIMR can scale up significantly in power, potentially generating continuous propulsion at levels high enough to carry large spacecraft across the solar system.

In 2015, NASA awarded Ad Astra a $9 million contract to further develop the VASIMR engine. The milestone: sustain 100 kilowatts of power for 100 continuous hours. Ad Astra delivered. But that’s just the beginning. The real vision? A 200-megawatt version that could, in theory, propel astronauts to Mars in just 39 days.

The concept isn’t just to reach Mars faster—it’s to make deep space travel viable. Because when you’re running on plasma instead of volatile rocket fuel, the possibilities grow exponentially. Mars becomes a stopover, not a destination. The outer planets become reachable in years, not lifetimes. And space travel itself starts to look a lot more like an interplanetary road trip—and less like a one-way ticket into the void.

How VASIMR Works: The Science Behind the Speed

At first glance, VASIMR might sound like a prop from a sci-fi novel—plasma jets, magnetic fields, radio waves—but the magic behind this engine is grounded in real, hard science. And while the physics gets intricate fast, the basic idea is elegantly simple: turn gas into plasma, superheat it, and use magnetic fields to fling it out the back of the spacecraft at incredible speed. This isn’t combustion. It’s controlled chaos turned into clean thrust.

It all starts with a puff of neutral gas—hydrogen, argon, or even xenon—fed into a cylindrical chamber lined with superconducting magnets. The first step is the “helicon stage.” Here, radio frequency (RF) waves from a special antenna—called the helicon coupler—excite the gas, stripping electrons from their atoms and turning it into a cloud of ionized particles known as plasma. This plasma is hot—about 5,800K, roughly the temperature of the Sun’s surface—but in VASIMR terms, it’s still considered “cold.”

Next comes the “ion cyclotron resonance heating” or ICRH stage, where things get seriously intense. Using techniques borrowed from fusion experiments, VASIMR bombards the plasma with another set of RF waves tuned to match the natural frequency at which the ions orbit the magnetic field lines. The result? A transfer of energy so efficient that the plasma’s temperature skyrockets to nearly 10 million degrees Kelvin—comparable to the Sun’s core.

But here’s the twist: unlike conventional rockets that blast hot gases out of a physical nozzle, VASIMR uses a magnetic nozzle. It’s a bit like shaping wind with invisible walls. The magnetic field guides the now-superheated plasma outward, converting the particles’ chaotic thermal motion into a focused stream of high-speed ions. These ions zip away from the spacecraft at up to 180,000 km/h (over 111,000 mph), generating thrust in the opposite direction and pushing the spacecraft forward.

And here’s where VASIMR really starts to shine: its flexibility. Engineers can adjust the amount of energy going into either the helicon or ICRH stages depending on the mission’s needs. Want to travel faster? Pump more power into the ICRH to boost speed, sacrificing some fuel efficiency. Need to conserve propellant? Dial down the energy and coast more gently. It’s essentially the cruise control of the cosmos.

One of the biggest advantages of this system is that nothing physically touches the plasma. In traditional engines, parts wear down from constant contact with hot exhaust. In VASIMR, the plasma is contained and steered entirely by magnetic fields, meaning no erosion, fewer breakdowns, and longer lifespans. That’s especially critical for deep-space missions where fixing a busted engine mid-flight isn’t exactly an option.

Add to that the fact that the fuel—light gases like hydrogen—could potentially be harvested from other celestial bodies, and you’re looking at a spacecraft that could refuel in orbit or on another planet. Combine this with a compact nuclear fusion reactor as a power source, and you’ve got a setup capable of sustaining high-thrust travel across vast distances without ever needing a pit stop back on Earth.

VASIMR vs. Other Propulsion Syste ms

Let’s start with the familiar: chemical rockets. These are the noisy giants that got us to the Moon and launched every Mars rover so far. They’re great at one thing—raw thrust. Need to escape Earth’s gravity? You’ll want a chemical rocket. But beyond that initial, powerful punch, they’re mostly dead weight. Once they burn through their massive fuel load, they coast. Efficient? Not even remotely. Flexible? Not at all. Chemical rockets are like drag racers—they’re fast off the line, but don’t ask them to go the distance.

Then there are ion drives. These have been the quiet achievers of space propulsion. They’ve powered satellites and deep space probes like NASA’s Dawn mission. Ion engines use electric fields to push charged particles out the back, providing steady but very low levels of thrust over long durations. They’re incredibly fuel-efficient—think Prius in space—but painfully slow to accelerate. Also, they can’t handle high power levels, which limits their usefulness for large-scale or crewed missions.

Hall-effect thrusters are another branch of the plasma family tree. They’ve been widely used for satellite positioning and orbital maneuvers. Like ion drives, they’re efficient and relatively simple, but they also suffer from limited thrust and scaling issues when we talk about interplanetary distances. They’re great at keeping satellites in line, not so much for sending astronauts to Mars.

Then there’s the Magnetoplasmadynamic Thruster (MPDT), a beast that once promised high-thrust plasma propulsion but came with its own issues—namely, it’s a power-hungry system with only modest efficiency gains. It’s also technically challenging to build and operate, and progress has been glacial since the 1960s.

And here’s where VASIMR takes the stage with a confident strut. Unlike ion or Hall thrusters, VASIMR doesn’t rely on physical electrodes touching plasma—eliminating a key wear-and-tear point. It also offers variable specific impulse, something no other propulsion system has managed effectively. In layman’s terms, it’s the only rocket engine that can shift gears in space—balancing speed and fuel efficiency based on mission needs.

VASIMR also scales beautifully. While many ion engines operate in the 1–10 kilowatt range, VASIMR has already demonstrated sustained operation at 100 kW—and aims for a whopping 200 MW in future designs. That’s not just a step up—it’s a leap into a whole new propulsion league.

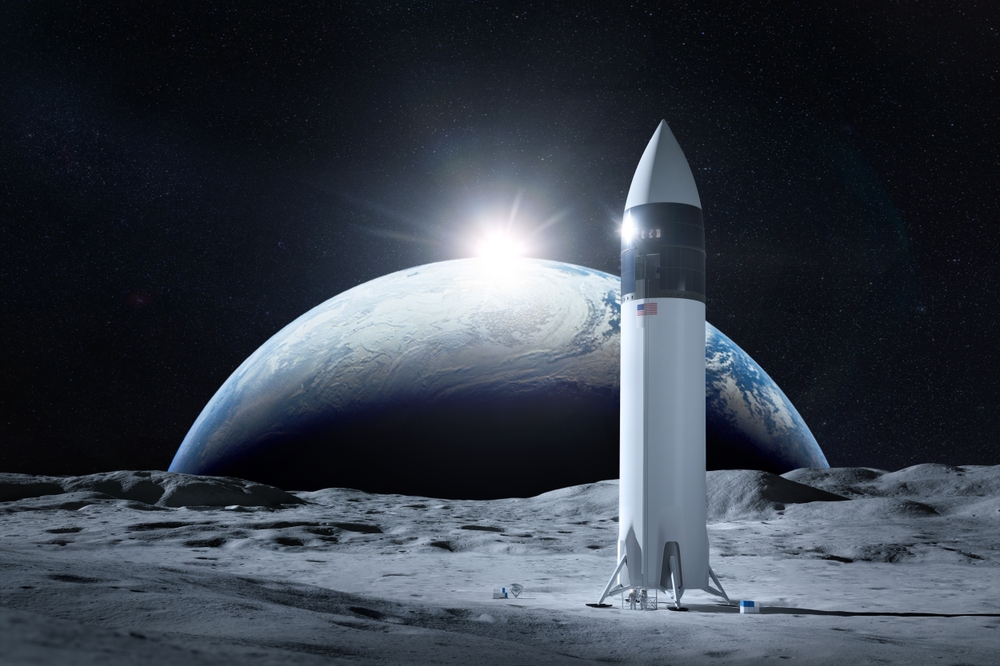

In essence, VASIMR isn’t trying to compete directly with chemical rockets for launch duty. It knows its role. It’s built for the deep vacuum of space, where sustained acceleration and adaptive power use matter most. It doesn’t replace chemical rockets—it complements them. A spacecraft could launch with a chemical booster, deploy in orbit, and then switch to VASIMR for the real journey ahead.

So while chemical rockets remain the burly lifters of the space world and ion engines the patient turtles of the interplanetary race, VASIMR might just be the sleek, high-speed hybrid that finally makes crewed deep-space travel not only possible but practical.

The 39-Day Mission: Is It Really Possible?

It sounds almost too good to be true—packing up a crew, launching into orbit, and making it all the way to Mars in just 39 days. That’s less time than it takes to get a passport renewed or finish a decent fitness challenge. Compared to the traditional 6–9 month voyage on a chemical rocket, the 39-day mission is a game-changing proposal that could redefine what we consider “long-distance” travel.

So, is it actually possible?

The short answer is: yes—theoretically. The long answer, as always in aerospace engineering, is: it’s complicated.

The 39-day figure comes from simulations based on a high-powered version of the VASIMR engine, one capable of sustained operation at 200 megawatts. This isn’t some random number plucked from a physics textbook—it’s based on a mission profile in which the spacecraft spends about 18 days accelerating, cruises at high velocity for 5 days, then begins a 16-day deceleration phase to gently meet Mars’ orbit. It’s not a rocket blast and coast. It’s a continuous push—like gradually flooring the gas pedal on an interplanetary autobahn.

In this scenario, VASIMR’s plasma engine doesn’t just give a brief burst of speed—it provides continuous propulsion over the course of the trip. That constant acceleration is key. Unlike chemical rockets, which fire once and let momentum do the rest, VASIMR keeps working throughout the journey, allowing the spacecraft to reach much higher speeds. At full throttle, it’s expected to reach velocities of up to 50 kilometers per second—over four times faster than conventional missions to Mars.

Now here comes the catch: powering such a journey isn’t as simple as plugging into a space outlet. A 200 MW power supply is no small ask. That’s the kind of juice needed to power a small city. Solar panels won’t cut it—they’d be far too heavy and inefficient for a mission of this magnitude. The most viable option is nuclear fusion, specifically a compact fusion reactor light enough to be launched into orbit but powerful enough to feed VASIMR’s insatiable energy needs. Companies like Lockheed Martin have proposed small-scale fusion reactors that could theoretically do the job, but these technologies are still under development.

There are also payload and mass considerations. A 39-day round-trip mission with VASIMR would require precise weight budgeting, including fuel (in the form of plasma-compatible gases), life support systems, radiation shielding, food supplies, and redundancy for critical systems. It’s a balancing act between efficiency and survivability.

And yet, despite all the engineering hurdles, there’s an irresistible logic to the idea. The faster you get to Mars, the safer your crew. Less time in space means lower radiation exposure, reduced muscle and bone degradation, and fewer opportunities for mechanical failures or psychological burnout. A quick sprint to Mars could make long-term missions far more feasible—not to mention less terrifying for the average astronaut.

Still, skepticism remains. Critics argue that Ad Astra’s current VASIMR prototypes, like the VX-200, aren’t yet capable of the levels of power and endurance needed for such a feat. And they’re right—today’s models are a far cry from the 200 MW behemoth required. But development continues. The proof-of-concept runs have been promising, and every successful test brings the dream a little closer.

Major Challenges and Controversies

Every technological breakthrough has its fair share of hurdles and skeptics, and VASIMR is no exception. As futuristic and promising as this plasma propulsion system sounds, it’s also tangled in a web of unresolved engineering questions, funding gaps, and, naturally, a little healthy scientific skepticism.

One of the first and most pressing challenges is that VASIMR cannot launch from Earth. It simply doesn’t have the thrust to escape our planet’s gravity. This isn’t a design flaw—it’s the nature of plasma engines. VASIMR excels in the vacuum of space, not in atmospheric drag. So any mission involving VASIMR would still need to piggyback off a traditional chemical rocket to reach orbit. Once in space, however, that’s where VASIMR takes over and shines. Still, this two-stage propulsion strategy introduces complexity in vehicle design and mission logistics.

Then there’s the elephant in the spacecraft: power. A fully realized 39-day Mars mission using VASIMR demands a power source of around 200 megawatts. For context, that’s enough to power over 100,000 homes. Solar power? Not even close—unless you want solar panels the size of a football stadium dragging behind you. A nuclear fission reactor is more realistic but comes with weight and safety concerns. Fusion reactors—lighter and more powerful—would be ideal, but they’re still in the experimental stage. Lockheed Martin’s container-sized fusion reactor concept is ambitious, but we’re still waiting on a working prototype that’s space-ready and launchable.

And while VASIMR’s technical specs are impressive on paper, some in the scientific community question the real-world feasibility of building a 200 MW version anytime soon. Critics argue that Ad Astra’s current engine, the VX-200, while remarkable, is still leagues away from the capability needed for human missions to Mars. There’s a significant difference between running 100 kW in a lab and sustaining megawatt-level power in the harsh environment of space, day after day, without failure.

There’s also some confusion that’s muddied public perception. Some early headlines misrepresented the technology, implying that VASIMR’s existing models could already make the Mars sprint. Ad Astra has clarified this repeatedly—no, the current engine cannot make the trip in 39 days. That would require future generations of the engine, powered by equally futuristic reactors. But the internet is notoriously bad at reading fine print, and this has led to unrealistic expectations and some disillusionment.

Funding is another quiet storm. Space propulsion doesn’t exactly grab the headlines the way rocket launches or Mars rovers do. Most government agencies and private investors want quick wins and splashy results. VASIMR’s development is a slow burn—requiring years of meticulous refinement and massive capital to build something that may not fly for decades. The question isn’t just can it be done, but will someone keep footing the bill long enough to see it through?

What VASIMR Could Mean for Humanity

Let’s start with the obvious: time. Reducing a journey to Mars from nine months to just over a month changes the rules of the game. It makes manned missions safer, faster, and significantly less expensive in the long term. Shorter missions mean less radiation exposure, less psychological strain, and fewer consumables needed onboard. That could drastically shift how we plan missions—making it possible to rotate crews more often, conduct rapid-response exploration, or even attempt emergency medical evacuations in extreme scenarios. In short, it turns Mars from a daring frontier into a reachable destination.

With scalable plasma propulsion systems like VASIMR, deep space ceases to be a once-in-a-generation challenge and becomes a matter of logistics and planning. Missions to Jupiter’s moons, asteroid mining expeditions, robotic reconnaissance of Saturn, or even long-haul cargo transport across the solar system become attainable—not in centuries, but in decades. Suddenly, a human presence beyond Earth isn’t limited to a single mission or moon base—it becomes sustainable.

VASIMR could also transform how we think about building and operating spacecraft. Without the heavy burden of chemical fuel tanks, spacecraft could be modular, lighter, and more versatile. Long-duration cargo freighters could be deployed to deliver materials to space stations, lunar bases, or future Martian outposts. Space could gain the equivalent of slow but steady delivery trucks—cheap, reusable, and always on the move.

Then there’s the tantalizing possibility of refuelling in space. Since VASIMR can use hydrogen—a substance abundant across the solar system—as fuel, it opens up the idea of ISRU (in-situ resource utilization). That means harvesting fuel from moons, comets, or even the atmospheres of gas giants. Imagine a spacecraft landing on Mars, scooping up hydrogen, and using it to power the trip back. It’s a self-sustaining ecosystem—a closed-loop system that dramatically cuts mission costs and increases independence from Earth.

And let’s not forget the symbolic weight of such an achievement. A functional VASIMR-powered mission to Mars would be a global milestone, inspiring generations much like the Moon landing did in 1969. It would prove that we can not only survive in space but thrive. That we can build cleaner, smarter propulsion systems. That we can set massive, borderline-unbelievable goals—and reach them.

Firing Up the Future

The path to Mars has always been paved with ambition, but never has it felt this close—or this fast. With VASIMR, we’re not just imagining faster travel; we’re engineering it. It’s a bold step away from the rocket-fueled muscle of the past and toward a future defined by precision, adaptability, and sustainability.

While challenges remain—especially in power generation and funding—the core idea of VASIMR has already disrupted how we think about propulsion. It invites us to dream of Mars not as a distant destination, but as a reachable waypoint. A place we can get to in weeks, not seasons.

What’s at stake isn’t just shorter trips—it’s the entire structure of space exploration. Faster transit means safer missions, more ambitious science, and a greater chance at building a real, lasting human presence beyond Earth. VASIMR, in many ways, represents the rocket engine version of human evolution—an intellectual leap forged not just by force, but by finesse.

The first journey to Mars in 39 days may not happen tomorrow. But if the engine’s hum ever replaces the roar of chemical fire as the soundtrack of deep space travel, we’ll look back on VASIMR not as a wild idea—but as the quiet, efficient pulse that carried us into a new era.

The countdown has already begun.