Seashells have it. Sunflowers have it. Even the spiral arms of hurricanes seem to follow it. For centuries, artists, mathematicians, and scientists have marveled at a simple number pattern that keeps showing up in the most unexpected places. Now, physicists have found it somewhere truly bizarre.

In a recent experiment, researchers fed an ancient mathematical sequence into a quantum computer. What happened next surprised everyone, including the scientists who designed the test. Fragile quantum information that normally survives for barely a second suddenly lasted nearly four times longer. And the explanation involves something that sounds like science fiction.

But before we get there, we need to talk about a number pattern that a medieval mathematician made famous over 800 years ago.

Nature’s Favorite Sequence

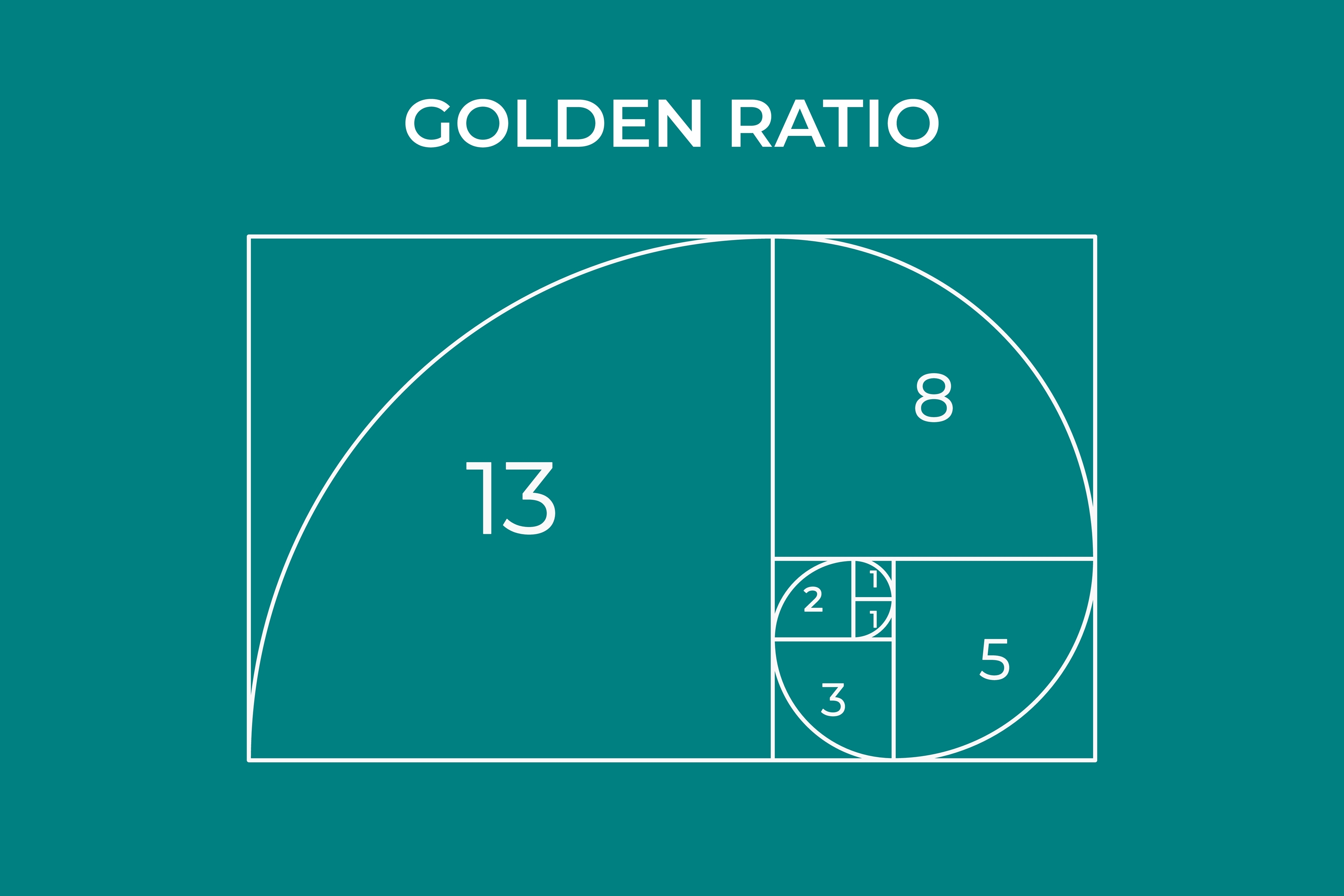

Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci, introduced a curious number pattern to Western mathematics in 1202. Each number in his sequence equals the sum of the two before it. Starting with zero and one, you get one, two, three, five, eight, thirteen, twenty-one, and so on forever.

At first glance, nothing about adding numbers together seems particularly exciting. Yet something strange happens when you look for Fibonacci numbers in the world around you.

Count the petals on a daisy. You will often find 34, 55, or 89 petals, all Fibonacci numbers. Look at how branches split on a tree or how seeds arrange themselves in a sunflower head. Fibonacci patterns appear again and again.

Why does nature love these numbers so much? Scientists believe it has something to do with efficiency. Plants that follow Fibonacci patterns can pack seeds more tightly or catch sunlight more effectively. Nature seems to favor patterns that balance structure with flexibility.

And here is where things get interesting for physicists. Quantum systems also need a balance between order and flexibility. Too much rigidity causes problems. Too much randomness creates chaos. Could Fibonacci patterns help quantum computers find that sweet spot? A team of researchers decided to find out.

Quantum Computers and Their Big Problem

Before we get to the experiment, you need to understand why quantum computers are both incredibly promising and incredibly frustrating.

Regular computers store information as bits. Each bit equals either a zero or a one. Simple enough. Quantum computers use something called qubits instead. A qubit can be zero, one, or both at the same time until you measure it.

Imagine flipping a coin that stays spinning in the air, somehow being both heads and tails until it lands. Qubits work a bit like that. Because they can hold multiple possibilities at once, quantum computers can explore many solutions to a problem simultaneously. Problems that would take regular computers thousands of years might take quantum computers just minutes.

Sounds amazing, right? Here is the catch.

Qubits are absurdly sensitive. Heat bothers them. Vibrations bother them. Electromagnetic noise bothers them. Even looking at them wrong, so to speak, can ruin everything.

Philipp Dumitrescu, a quantum physicist who led the theoretical side of the recent experiment, put it plainly. “Even if you keep all the atoms under tight control, they can lose their quantumness by talking to their environment, heating up or interacting with things in ways you didn’t plan.”

When qubits lose their quantum properties, scientists call it decoherence. All that special information disappears. Most quantum systems lose coherence in tiny fractions of a second. Getting qubits to stay quantum even slightly longer counts as a major victory.

Engineers can build qubits. They can manipulate them. But keeping them stable long enough to do useful work? Painfully difficult.

A Ten-Atom Experiment Changes Everything

Researchers at Quantinuum, a quantum computing company in Colorado, teamed up with theorists to try something unconventional. Instead of working with a massive machine, they set up a careful experiment using just ten atoms of ytterbium, a silvery metal, arranged in a straight line. Each atom acted as a single qubit.

Laser pulses controlled how these qubits behaved over time. Normally, researchers apply laser pulses at regular intervals, like a metronome keeping steady time. Tick, tick, tick.

Dumitrescu and his collaborators wondered what would happen if they changed the rhythm. Instead of evenly spaced pulses, they timed the laser blasts according to the Fibonacci sequence. Pulse A, then pulse B, then A-B, then A-B-A, then A-B-A-A-B, building outward following Fibonacci’s pattern.

Regular periodic pulses kept the edge qubits quantum for about 1.5 seconds. Not bad for quantum computing standards.

Fibonacci-patterned pulses? The edge qubits stayed quantum for 5.5 seconds, the entire length of the experiment. Nearly four times longer.

Something about that ancient number pattern was protecting quantum information in ways no one had seen before.

Two Directions of Time in One Dimension

So why did Fibonacci pulses work so much better? Dumitrescu offered an explanation that sounds almost impossible. “What we realized is that by using quasi-periodic sequences based on the Fibonacci pattern, you can have the system behave as if there are two distinct directions of time.”

Wait, what? Let’s break that down. Regular laser pulses repeat in a simple cycle. A, B, A, B, A, B, and so on. Fibonacci pulses follow a pattern, but that pattern never actually repeats. Mathematicians call patterns like these quasiperiodic. Ordered, but not repeating.

You might have seen quasicrystals before, even if you did not know the name. Penrose tilings, those mesmerizing geometric patterns that cover a surface without ever repeating, are one example. Quasicrystals exist in physical materials too, discovered in laboratories and even in meteorites.

Here is the wild part. Quasicrystals can be understood as projections from higher dimensions. A two-dimensional Penrose tiling, for instance, is essentially a slice of a five-dimensional structure squished down into our flat world.

By pulsing lasers in a Fibonacci pattern, the researchers created something similar, but in time rather than space. A quasicrystal in time. And because of how these patterns work mathematically, the system gains symmetry from a dimension that does not physically exist. One flow of time. Two-time symmetries. Mind-bending stuff.

Why Edge Qubits Stayed Protected

All of this theoretical weirdness served a practical purpose. Extra symmetry means extra protection. In quantum systems, errors accumulate over time. Small disturbances add up, eventually destroying the delicate quantum states researchers work so hard to maintain. Physicists have tried imposing strict order on qubits, using precise timing and rigid control sequences to fight back against errors. Fibonacci pulses offered a different approach. Structured unpredictability.

“With this quasi-periodic sequence, there’s a complicated evolution that cancels out all the errors that live on the edge,” Dumitrescu explained. “Because of that, the edge stays quantum-mechanically coherent much, much longer than you’d expect.”

Edge qubits, the atoms at either end of the ten-atom lineup, benefited most from this effect. Errors that would normally build up and destroy quantum information instead got canceled out by the evolving Fibonacci pattern. Like noise-canceling headphones for quantum states.

A New Phase of Matter Emerges

When physicists see particles behaving collectively in strange new ways, they often describe the result as a new phase of matter. We all know about solids, liquids, and gases. Quantum physics allows for far stranger possibilities.

What the researchers created falls into a category called a temporal quasicrystal. A regular crystal repeats the same atomic pattern over and over in space. A quasicrystal has a structure but never repeats. A temporal quasicrystal does the same thing, but in time rather than space.

Nobody had observed this particular phase before. And it came with a bonus. Information stored in this phase resisted errors far better than current quantum computing methods allow.

What Longer Coherence Means for Real-World Applications

Okay, so physicists made qubits last longer using a medieval number pattern. Why should anyone outside a physics lab care?

Quantum computers promise to solve problems that regular computers simply cannot handle. Drug discovery, for example. Simulating how molecules interact at a quantum level could help researchers design new medicines far faster than current methods allow.

Climate modeling, materials science, cryptography, and financial modeling could all benefit from quantum computing power. But all these applications depend on qubits staying quantum long enough to finish calculations.

Right now, most quantum computers lose coherence so quickly that they can only run very short programs. Errors pile up. Calculations fall apart before producing useful results.

If Fibonacci-based timing can scale up to larger systems, it could help quantum computers run longer and more reliably. Problems that seem impossible today might become routine tomorrow.

A Shift in How Scientists Think About Control

For years, quantum engineers tried to impose strict order on qubits. Precise timing. Rigid schedules. Repetitive control sequences. Beat the chaos into submission.

Fibonacci pulses suggest a different philosophy. Instead of forcing order, allow structured unpredictability. Guidance without repetition. Stability without rigidity.

Nature operates this way all the time. Biological systems thrive on patterns that balance order and variation. Hearts beat rhythmically but not perfectly metronomically. Brain waves follow patterns that shift and adapt. Maybe quantum systems benefit from similar flexibility.

From Medieval Math to Future Machines

Leonardo of Pisa introduced his sequence to help European merchants calculate currency exchanges more efficiently. He could never have imagined lasers, atoms trapped in electric fields, or computers that process information using quantum mechanics. Yet here we are. A number pattern from 1202 might help build the computers of 2030 and beyond.

Sometimes progress comes not from adding complexity but from choosing the right pattern. Scientists did not invent new hardware or develop exotic new materials. They simply changed the rhythm of their laser pulses to match a sequence humanity has known for centuries.

A Sequence Still Unfolding

Quantum computers may one day run on rhythms that medieval mathematicians would recognize. Patterns found in flower petals and seashells might quietly guide the machines solving problems we cannot even imagine yet.

For now, a small experiment with ten atoms has shown that sometimes the best solutions come from unexpected places. Ancient math. Natural patterns. A willingness to try something different.

Leonardo of Pisa probably never dreamed his number sequence would help protect information in devices that manipulate reality at its smallest scales. But science has a way of connecting ideas across centuries. And quantum computers, it turns out, might have been waiting for Fibonacci all along.