Metformin is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the world. It is inexpensive, has been around for decades, and is rarely thought of as anything more than a routine diabetes medication. But that quiet reputation may be starting to change.

Researchers are now paying attention to this drug for a reason that has nothing to do with blood sugar. Early findings have raised new questions about whether it could play an unexpected role in one of the most challenging areas of cancer treatment, and why certain tumors may be especially affected.

What scientists are seeing so far is not definitive, and it is not ready for clinical use. But it has been enough to shift how some researchers think about this long standing medication and to prompt a closer look at what it may be doing beyond its original purpose.

Why Metformin Is Getting Attention Beyond Diabetes

Interest in metformin beyond diabetes emerged from population level data rather than laboratory experiments. Over time, analyses of large health databases repeatedly showed that people with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin were diagnosed with certain cancers less often than those using other glucose lowering medications. This pattern appeared across multiple countries and study designs, making it difficult to attribute to chance alone.

What drew particular attention was the persistence of these associations even after researchers adjusted for age, body weight, smoking status, and diabetes severity. While these studies could not establish causation, they suggested that metformin might be influencing cancer risk through mechanisms unrelated to blood sugar control.

Metformin also stood out for practical reasons. It is already approved, inexpensive, and supported by decades of human safety data. For cancer researchers, that combination makes it a strong candidate for repurposing, allowing investigations to move more quickly from epidemiologic signals to targeted biological questions without the delays associated with developing new drugs from scratch.

New Research Focuses on Hard-to-Treat Colon Cancers

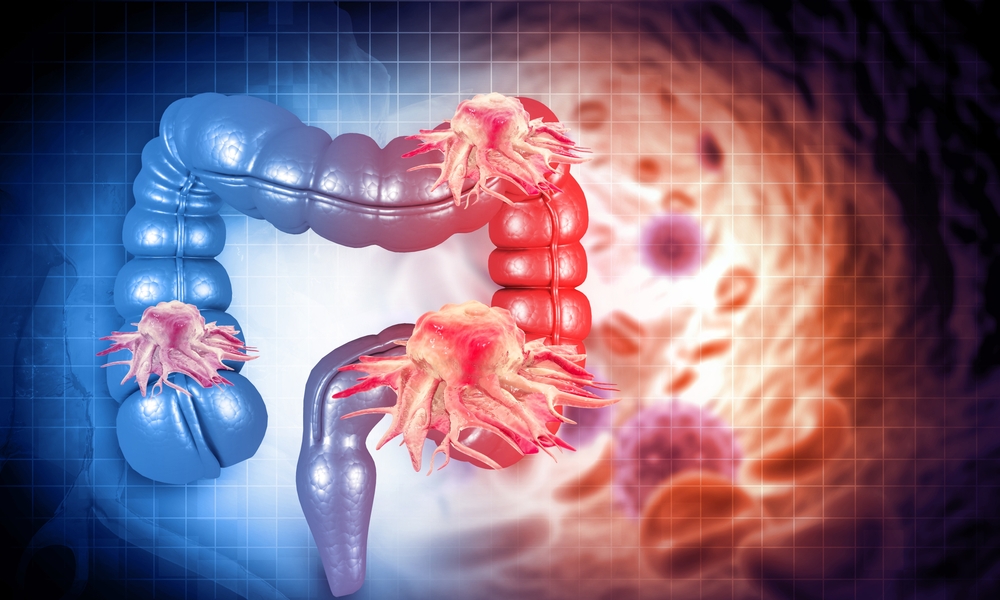

At the 2025 American Association for Cancer Research conference in Chicago, researchers from The Ohio State University presented early laboratory findings examining how metformin interacts with specific subtypes of colon cancer cells rather than colorectal cancer as a whole. The focus was deliberate. Instead of looking for broad anticancer effects, the team concentrated on tumors with molecular features that have historically limited treatment success.

One of those features is mutation status. Certain genetic alterations are strongly linked to treatment resistance and poorer outcomes in colorectal cancer, and these tumors are often underrepresented in early drug development pipelines because they are harder to target. By centering the research on these more challenging cancer profiles, investigators aimed to test whether metformin showed any selective activity where standard approaches tend to fall short.

Holli Loomans-Kropp, a gastrointestinal cancer prevention researcher at The Ohio State University and lead investigator on the project, emphasized that the work is exploratory and intended to expand therapeutic options rather than replace existing care. In an interview with Business Insider, she said, “Metformin seems like it could have a really interesting supplemental approach to therapy. We’re opening up some doors to what this could do.”

This strategy aligns with a broader shift in cancer research toward identifying supportive therapies that may enhance current treatment responses rather than compete with them. A review in Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology discusses how targeting metabolic vulnerabilities in difficult to treat colorectal cancers has become an active area of investigation, particularly for tumors with limited targeted therapy options.

How Metformin May Interfere With Cancer Cell Metabolism

Cancer cells need a steady supply of energy to keep growing and dividing. One reason metformin has drawn interest is that it interferes with how cells manage that energy supply, creating conditions that are less favorable for rapid growth.

At a basic level, metformin affects the cell’s power system. It reduces how efficiently cells produce energy, which can leave them in a low energy state. When this happens, cells tend to slow down activities that require a lot of fuel, including processes involved in growth and division. Researchers often describe this as putting the cell into a conserve mode rather than a growth mode.

Metformin also influences how cells respond to signals that normally encourage growth. When energy is low, internal signaling shifts away from building and expansion and toward maintenance. In cancer cells that already operate near their metabolic limits, this shift may make it harder to sustain fast growth, especially when combined with other treatments.

Researchers are careful to note important limitations. Many laboratory studies test conditions that do not perfectly match what happens in the human body, and not all tumors respond the same way. That is why these findings are considered supportive evidence rather than proof of benefit, and why controlled clinical trials are needed to determine whether these metabolic effects translate into meaningful outcomes for patients.

What This Means for People With KRAS Mutations

KRAS mutations are common in colorectal cancer and are often linked to tumors that are harder to control with existing treatments. For patients, this usually means fewer effective targeted drug options and greater reliance on surgery and chemotherapy, which do not work equally well for everyone.

What makes the metformin research relevant here is not that it targets the KRAS mutation itself, but that it may affect vulnerabilities shared by these tumors. Cancers driven by KRAS tend to place heavy demands on their internal energy systems. Approaches that interfere with how these cells manage energy may therefore have a greater impact than treatments aimed at single growth signals. This helps explain why researchers are exploring whether metformin could act as a supportive therapy rather than a stand-alone treatment.

For now, these ideas remain based on laboratory observations. There is no evidence yet that metformin improves outcomes for people with KRAS mutated colon cancer, and it is not part of standard care. The importance of this research lies in opening potential paths for patients who currently have limited options, while reinforcing the need for carefully designed clinical trials before any changes to treatment recommendations are considered.

What Still Needs to Happen Before Metformin Is Used in Cancer Treatment

For metformin to move from an interesting research lead to something doctors could reasonably add to colon cancer care, it has to clear several evidence checkpoints. The first is confirming that the effects seen in isolated cells also show up in living systems, where tumors interact with blood supply, the immune system, and surrounding tissue. That stage helps researchers answer a basic question that lab work cannot fully settle: does the drug reach tumors in a meaningful way and produce measurable biological changes under real world conditions.

The next step is defining how metformin would be used alongside standard care. That includes determining the dose and schedule that are realistic and safe for people who may already be dealing with side effects from chemotherapy or other treatments. Researchers also need to clarify who would be most likely to benefit, because colorectal cancer is not a single disease and responses can vary widely based on tumor features and patient health.

Finally, well designed human trials have to show that adding metformin changes outcomes that matter, such as tumor response, recurrence, or survival, and that any benefits outweigh added risks. Even a medication with a long track record can behave differently in a new context, especially in patients who are not taking it for diabetes. Until those trials are completed and replicated, metformin remains a candidate for research, not a routine part of cancer treatment.

What Readers Should Know Right Now

The most important takeaway at this stage is restraint. Metformin is not approved for cancer treatment or prevention in people without diabetes, and current findings do not justify self experimentation or off label use. Laboratory results are designed to guide future studies, not clinical decisions.

This research also highlights how early stage cancer science typically unfolds. Signals first appear in population data or lab models, then move slowly through testing stages designed to protect patients from unproven interventions. That process can feel frustratingly slow, but it exists to separate promising ideas from treatments that truly improve outcomes.

For individuals concerned about colon cancer risk today, the most reliable actions remain unchanged. Regular screening, attention to persistent symptoms, and lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, and smoking avoidance have far stronger evidence behind them than any repurposed medication still under investigation. New research may expand options in the future, but it does not replace what is already known to work.

A Familiar Drug Worth Watching

The idea that a 20-cent diabetes drug could help change how we treat colon cancer is compelling, but it’s not a reason for premature conclusions. What makes metformin worth watching is the combination of biological plausibility, observational data, and early laboratory evidence pointing in the same direction.

If future trials confirm these effects in people, metformin could become a low-cost, accessible addition to existing cancer therapies, particularly for patients with limited treatment options. Until then, it remains a promising research avenue rather than a clinical solution.