Greenland keeps secrets. Beneath its massive ice sheet and along its rugged coastlines lies a geological story that spans nearly four billion years. Most people picture endless white when they imagine the world’s largest island. Few realize what treasures sit locked in its ancient rocks.

Recent global attention has turned toward Greenland for reasons beyond its stunning fjords and Arctic wildlife. Scientists, governments, and mining companies have all begun asking the same question. What exactly makes this remote island so valuable?

Jonathan Paul, an associate professor in Earth Science at Royal Holloway, University of London, has spent years studying Greenland’s geological makeup. His findings reveal an island unlike any other on Earth. From rocks older than most life forms to mineral deposits that could reshape global markets, Greenland presents opportunities and dilemmas that few places can match.

A Timeline Written in Stone

Nearly four billion years of geological history have shaped Greenland into what it is today. Some of Earth’s oldest rocks can be found near Nuuk, the capital city. Scientists have dated certain formations in the Isukasia area to 3.8 billion years old, making them among the most ancient rocks anywhere on the planet.

But age alone does not make Greenland special. What sets it apart is how many different geological processes have worked on this single landmass over billions of years.

Paul explains why geologists find Greenland so fascinating. “Geologically speaking, it is highly unusual (and exciting for geologists like me) for one area to have experienced all three key ways that natural resources – from oil and gas to REEs and gems – are generated.” REEs refer to rare earth elements, materials now considered essential for modern technology.

Mountain-building events compressed and fractured Greenland’s crust over millions of years. Gold, rubies, and graphite settled into these faults and fractures. Rifting periods, including the formation of the Atlantic Ocean more than 200 million years ago, created conditions for oil and gas deposits. Volcanic activity added yet another layer of mineral wealth, depositing rare earth elements in igneous rock formations.

Few places on Earth can claim all three processes. Greenland has experienced them repeatedly throughout its long history.

Hidden Wealth in Ancient Rocks

Greenland’s ice-free zones reveal only a fraction of what the island contains. Truck-sized lumps of native iron, not delivered by meteorites but formed within the Earth itself, dot certain landscapes. Diamond-bearing kimberlite pipes were discovered back in the 1970s, but remain untouched because getting to them and mining them presents enormous logistical challenges.

Sedimentary basins hold promise for oil and gas. US Geological Survey estimates suggest that onshore northeast Greenland contains around 31 billion barrels of oil-equivalent in hydrocarbons. For perspective, that figure matches America’s entire volume of proven crude oil reserves. Researchers believe extensive petroleum systems may ring the entire offshore coastline, though high costs have prevented serious commercial exploration.

Base metals like lead, copper, iron, and zinc have been mined on a small scale since 1780. Gold mining operated successfully at Nalunaq in South Greenland from 2004 to 2013, producing over 11 tonnes of gold before market conditions forced closure.

Yet Greenland’s most strategic resources may be its rare earth elements. Deposits of niobium, tantalum, and ytterbium sit within igneous rock layers. Even more important are reserves of dysprosium and neodymium, two elements considered among the hardest to source anywhere in the world. Greenland may hold enough of these materials to satisfy more than a quarter of predicted future global demand, a combined total approaching 40 million tonnes.

Wind turbines, electric vehicle motors, and magnets used in nuclear reactors all require these elements. As the world races toward cleaner energy, the materials needed to build that future increasingly point toward Greenland.

Where Ice Meets Opportunity

Here lies Greenland’s great paradox. Ice covers roughly 80 percent of the island’s surface. Only about 410,000 square kilometers remain ice-free, an area nearly double the size of the United Kingdom. Everything described so far comes from less than one-fifth of Greenland’s total surface.

What resources might exist beneath kilometers of ice? No one knows for certain, but geological models suggest vast, unexplored stores of minerals and hydrocarbons remain hidden under the frozen blanket.

Climate change has begun shifting these calculations. “An area the size of Albania has melted since 1995, and this trend is likely to accelerate unless global carbon emissions fall sharply in the near future.” The ice that took thousands of years to form now disappears decade by decade, gradually exposing new terrain for potential exploration.

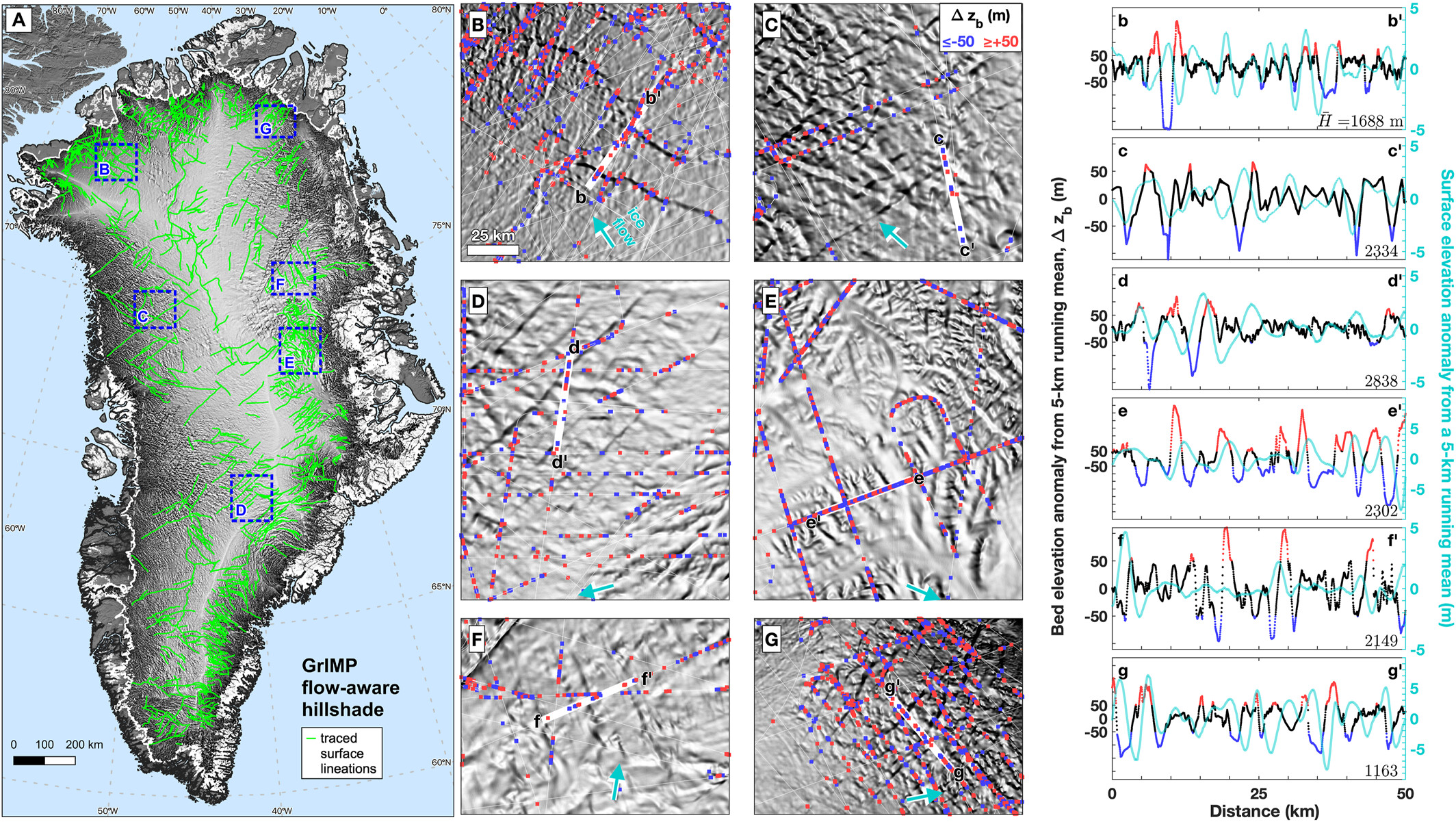

Ground-penetrating radar technology has advanced significantly in recent years. Scientists can now peer beneath up to two kilometers of ice to map bedrock topography. These surveys provide clues about what mineral resources might exist in Greenland’s subsurface. However, prospecting under ice moves slowly, and sustainable extraction from such environments will prove even more difficult.

A Mining History That Barely Scratches the Surface

Despite all this potential, actual mining in Greenland has remained limited. “A relatively weak record of mining activity appears to contrast with the metal endowment and existence of numerous mineral occurrences and several world class mineral deposits.” A study commissioned by Finland’s Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment reached this conclusion after examining Greenland’s mining history and future prospects.

Why the gap between potential and production? Several factors combine to create challenges that have deterred investment.

Greenland has no roads connecting its towns and settlements. Every mine site requires its own infrastructure, including power generation, water treatment, housing, and transportation links. Helicopter and boat support drive up costs during exploration phases. Harsh Arctic weather limits working seasons. Finding skilled workers presents another obstacle, as Greenland’s population of roughly 56,000 people cannot supply the labor force that large mining operations require.

Currently, only two mines operate in Greenland. A ruby mine at Aappaluttoq began production in 2017. An anorthosite mine at White Mountain started operating in 2018, producing industrial minerals used in fiberglass manufacturing. Neither has yet demonstrated consistent profitability.

Several other projects hold exploitation licenses but await better market conditions or additional financing. A zinc and lead deposit at Citronen Fjord in North Greenland ranks among the world’s largest undeveloped resources of its kind. Rare earth projects in South Greenland have progressed through environmental assessments and inch toward production decisions.

Green Energy’s Uncomfortable Truth

Modern society increasingly depends on materials that Greenland possesses in abundance. Solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and energy storage systems all require rare earth elements and other specialty metals. Reducing carbon emissions means building massive amounts of clean energy infrastructure, and building that infrastructure requires mining.

Greenland sits at the uncomfortable intersection of environmental protection and environmental necessity. Extracting its resources would support the global energy transition. Yet mining inevitably damages landscapes, and in Greenland’s case, it would affect one of Earth’s last pristine wilderness areas.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity. Melting ice makes more resources accessible while simultaneously threatening coastal communities with rising sea levels. Greenland’s ice sheet contains enough frozen water to raise global sea levels by about seven meters if it melted completely. Every year of accelerated melting brings that scenario closer to reality.

Resource extraction in Greenland would generate economic benefits for a population seeking greater independence from Denmark. Fishing currently accounts for about 90 percent of exported goods, leaving the economy vulnerable to shifts in fish populations and market prices. Mining revenue could diversify income sources and fund social programs. But at what environmental cost? And who should make these decisions?

Regulation, Politics, and an Uncertain Future

Greenland has regulated mining activities through legal frameworks dating back to the 1970s. Environmental impact assessments, social impact studies, and benefit agreements with local communities must all be completed before exploitation licenses are granted. Royalties on extracted minerals range from 2.5 to 5.5 percent, depending on the commodity.

Self-governance expanded significantly in 2009 when Greenland gained authority over its mineral resources. A path toward potential independence from Denmark remains open, though the timeline and conditions remain subjects of ongoing debate among Greenland’s political parties.

International interest has grown considerably. American attention toward Greenland made headlines when discussions about purchasing the island surfaced in 2019. More recently, the United States has allocated funding for consulting projects and advisory assistance focused on tourism, mining, and education in Greenland. A new American consulate opened in Nuuk, signaling increased diplomatic engagement.

China has also shown interest, with a Hong Kong-based conglomerate acquiring rights to a major iron ore project, though that development remains stalled due to market conditions.

Pressure to loosen environmental controls and grant new exploration licenses may increase as global competition for critical minerals intensifies. Greenland’s government faces difficult choices about balancing economic development against environmental protection, local interests against international pressures, and short-term gains against long-term consequences.

When the Ice Reveals Its Secrets

Greenland stands at a crossroads that will shape its future for generations. Beneath its ice and within its ancient rocks lie materials the world desperately wants. Getting them out presents challenges that range from logistical to ethical.

For geologists like Jonathan Paul, the island represents a scientific wonderland, a place where nearly four billion years of Earth’s history remain visible and accessible. For policymakers, it represents strategic importance in an era of energy transition. For Greenlanders themselves, it represents home, tradition, and an uncertain path forward.

No easy answers exist. Climate change will continue exposing new areas while threatening existing communities. Global demand for rare earth elements will keep growing. International attention will not fade.

Whatever decisions emerge in the coming years will carry consequences far beyond Greenland’s shores. An island that few people could locate on a map may help determine whether the world successfully transitions to cleaner energy or stumbles in the attempt. Greenland keeps secrets. Soon, it may have to reveal them.