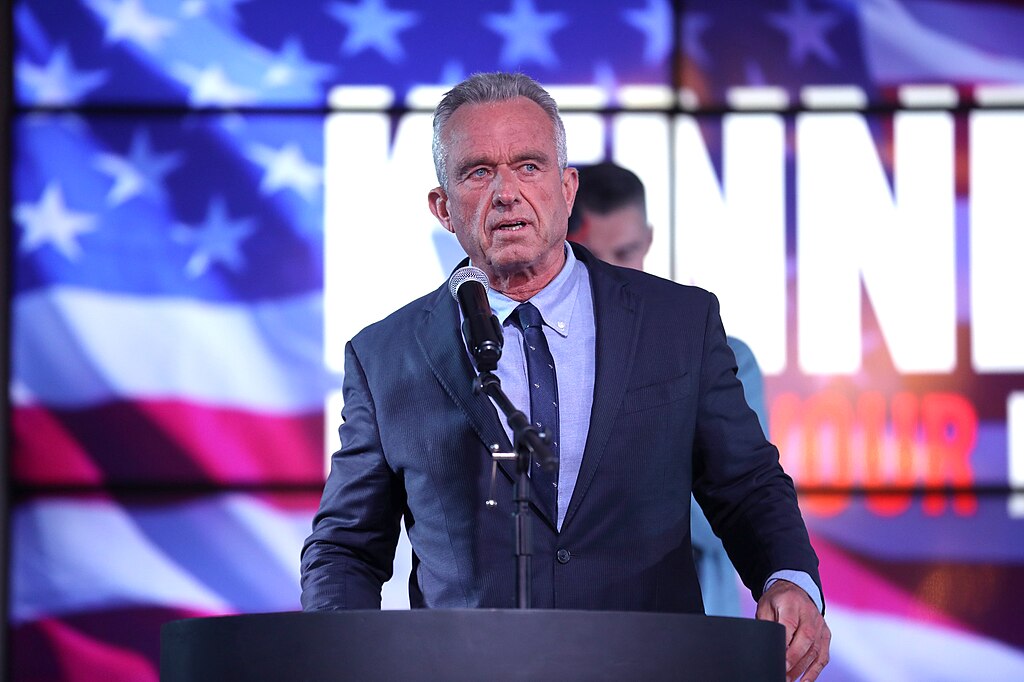

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has spent much of his public life fighting what he sees as outdated systems that harm both people and the planet. As Health Secretary in the Trump administration, he’s now taken that battle to the heart of biomedical research calling for a complete phaseout of animal testing for chemicals and drugs in the United States.

His initiative, part of his “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA) agenda, proposes something radical: replacing animal testing with human-based technologies such as organoids, computer modeling, and lab-grown tissue systems. Kennedy describes it as a scientific evolution long overdue and a moral reckoning that can no longer be ignored.

What makes this policy fascinating is not only its ambition but its strange political chemistry. Kennedy, a figure often at odds with mainstream science, now finds himself uniting conservatives, animal rights activists, and reform-minded scientists behind a single vision: the end of animal suffering in American research.

The Ethical and Scientific Case Against Animal Testing

Animal testing has been the backbone of drug and chemical development for over a century. Every major pharmaceutical advancement from insulin to chemotherapy was once tested on animals. But that legacy is under increasing scrutiny.

Critics argue that while animal testing once filled an important scientific gap, it has outlived its usefulness. The biological differences between animals and humans, they say, make such experiments unreliable and often misleading. Drugs that appear safe in rodents or monkeys frequently fail when tested in people. According to the Food and Drug Administration, about 90 percent of drugs that enter clinical trials never reach the market, largely because results from animal studies don’t translate to human biology.

Kennedy has seized on this inefficiency to argue that sticking with animal models is both cruel and unscientific. “We’re spending billions on research that doesn’t deliver results,” he said at a recent press event. “We can do better for science, for health, and for animals.”

The ethical argument is equally powerful. Millions of animals each year are subjected to painful experiments with little chance of survival. Many are bred for this purpose, kept in sterile labs, and euthanized once the tests conclude. Kennedy’s plan would not only reduce their use but also fund rehoming programs for retired lab animals a humane gesture that reflects the shifting values of the American public.

A Technological Revolution in the Making

The backbone of Kennedy’s proposal is technological innovation. The National Institutes of Health, now under his oversight, recently established the Standardized Organoid Modeling (SOM) Center at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research. The 87 million dollar project will develop and standardize “organoid” technology clusters of human cells grown to replicate the functions of organs like the liver, brain, or heart.

These miniature organ models allow researchers to study diseases and test drugs in environments that mimic human biology far more accurately than animal systems. Scientists can even grow organoids from a patient’s own cells, making it possible to predict how that person might respond to a treatment before ever taking a pill.

Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, the NIH director, described the SOM Center as “a bridge between ethics and innovation.” He believes these human-based systems will eventually make animal testing obsolete by offering faster, cheaper, and more precise insights into how chemicals and drugs affect the body.

Computer simulations, artificial intelligence, and 3D bioprinting are also part of Kennedy’s toolkit. Together, these technologies could usher in a new era of predictive modeling one where scientists no longer have to rely on the suffering of sentient creatures to understand human biology.

Politics, Compassion, and Strategy

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of Kennedy’s initiative is how it has reshaped the political landscape around animal rights. Once considered a left-wing cause, animal welfare is increasingly becoming a bipartisan issue.

Kennedy’s MAHA program aligns comfortably with Trump’s populist messaging: protecting taxpayers, modernizing science, and emphasizing American innovation. The administration’s outreach to animal rights advocates, including groups like PETA and White Coat Waste, demonstrates a pragmatic recognition that compassion is politically marketable.

Laura Loomer, a conservative activist known for her alignment with the MAGA movement, called the initiative “a unifying cause that transcends ideology.” Polling data supports her claim more than 80 percent of Americans favor reducing or eliminating animal testing, regardless of party affiliation.

Trump, never known as an environmentalist, has nonetheless presided over a surprisingly pro-animal record. During his first term, he signed multiple laws targeting cruelty in horse racing and pet trade practices. Kennedy’s reform builds on that legacy while giving it a scientific and moral dimension.

For Kennedy, the politics seem secondary to the principle. “This isn’t about left or right,” he said. “It’s about doing what’s right and what works.”

Pushback From the Scientific Establishment

Not everyone shares Kennedy’s optimism. Traditional researchers warn that abandoning animal models too quickly could slow medical progress and jeopardize public safety.

Naomi Charalambakis, a policy expert at Americans for Medical Progress, cautions that organoids and computer simulations still lack the complexity of living organisms. “They can’t yet replicate the immune system, metabolism, or long-term toxicity effects that we see in animals,” she said.

Others in the biomedical community fear that political enthusiasm could outpace scientific readiness. Drug development, they argue, is already fraught with risks moving too fast toward untested alternatives might create new ones.

Kennedy’s team has acknowledged these challenges but insists that incremental change is possible without halting critical research. The NIH’s strategy focuses first on areas where animal testing is least predictive, such as toxicity screening and certain neurological studies. Over time, as new technologies mature, they could replace more complex animal models altogether.

The scientific world has been slow to change, partly because of financial incentives. Animal-based research is a massive industry involving labs, breeders, and suppliers. Redirecting federal funding toward human-based methods threatens established revenue streams. In that sense, Kennedy’s initiative isn’t just a moral challenge it’s an economic one.

From Policy to Philosophy

The debate over animal testing reaches beyond laboratories. It touches on how society defines progress, compassion, and responsibility.

Kennedy’s approach embodies what might be called “ethical modernization” the idea that technological advancement must evolve alongside moral understanding. His argument is not anti-science; it’s pro-human science. By promoting models based on human biology, he aims to align research with reality and conscience simultaneously.

The MAHA initiative also connects with Kennedy’s long-standing environmental philosophy. As a lawyer, he spent years fighting corporate pollution and advocating for ecosystems harmed by industrial excess. In that light, his opposition to animal testing is part of a larger worldview: that human health cannot be separated from ethical stewardship of life.

In a speech unveiling the SOM Center, Kennedy said, “Our health system can’t claim to be humane while it depends on cruelty. The path to better science begins with empathy.”

This blending of moral and scientific rhetoric has proven unusually resonant in today’s polarized political climate. It appeals to conservatives’ distrust of bureaucratic inefficiency and to progressives’ commitment to compassion and reform.

A Clash Between Tradition and Transformation

Kennedy’s policy has sparked an internal debate within the administration itself. Some officials worry that moving too far, too fast could alienate pharmaceutical donors or complicate relationships with research institutions. Others see the initiative as an opportunity to demonstrate that the government can modernize responsibly without sacrificing ethical standards.

Trump himself has reportedly expressed cautious support, viewing the animal testing issue as a chance to connect with new voter blocs, including younger Americans and suburban moderates who prioritize animal welfare. “It’s an issue everyone can agree on,” one campaign strategist told POLITICO. “It softens his image without changing his brand.”

Meanwhile, advocacy groups that have historically battled the NIH are now working with it. PETA sent flowers to NIH Director Bhattacharya earlier this year, praising his leadership a gesture that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago.

Still, tensions remain. Some conservative activists, including Loomer, accuse the administration of “moving too slowly” and claim that Kennedy’s advisors are overly deferential to entrenched scientific interests. The controversy has even spilled into social media battles and conference confrontations, underscoring how emotionally charged the issue has become.

Building a Future Beyond Animal Testing

Ending animal testing will not happen overnight. It requires new infrastructure, updated regulations, and cultural change within the scientific community. Yet small victories are already accumulating.

The FDA Modernization Act 2.0, signed into law before Kennedy’s appointment, removed the requirement that drugs be tested on animals before human trials. That legal shift opened the door for new methods like organoids and AI modeling to gain legitimacy. Kennedy’s SOM Center builds on this foundation by setting national standards for these technologies a critical step toward regulatory acceptance.

Advances are happening worldwide as well. The European Union has funded extensive research into human-based alternatives, and several countries, including the Netherlands, have pledged to eliminate animal testing for safety studies by the end of the decade. The U.S., under Kennedy’s guidance, appears poised to catch up.

In the long term, Kennedy envisions a research ecosystem built on precision, transparency, and compassion. “When we stop hurting animals,” he said, “we start healing the system.”

The Moral of the Movement

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s campaign to end animal testing represents a convergence of ethics, science, and politics rarely seen in modern policymaking. It has forced both parties to reconsider their assumptions about progress and reminded scientists that morality is not the enemy of discovery.

Critics may argue that Kennedy’s plan is too idealistic, but history often rewards idealists who are patient enough to turn conviction into practice. Whether or not animal testing disappears in the next decade, his initiative has already achieved something significant: it has reframed the national conversation around what humane science looks like.

The MAHA agenda, often dismissed as rhetorical, may yet become a blueprint for reform that endures beyond any single administration. If Kennedy’s vision succeeds, it won’t just change how America develops medicine. It will change what it means to be a scientific nation in the twenty-first century one that values empathy as much as evidence.

In that sense, Kennedy’s push is more than a bureaucratic reform. It is a reminder that progress is not measured solely in patents or profit, but in how we choose to wield our intelligence. The real experiment, perhaps, is not in the lab but in our capacity for compassion.