For years, multiple sclerosis (MS) has left scientists, doctors, and patients alike scratching their heads. It’s a condition that seems to appear out of nowhere—unpredictable, incurable, and often misunderstood. We’ve blamed everything from viruses to vitamin deficiencies, genetics to geography. But what if the answer has been hiding much closer to home all along—deep in your gut?

That’s right. A new wave of research is flipping the script on how we think about MS. And it’s not just another theory tossed into the mix—this time, scientists may have found something (or rather, someone) specific.

Spoiler: it’s not what you’d expect.

Keep reading to find out how our tiniest tenants—gut bacteria—might be stirring up big trouble in the brain. And why this discovery could change the way we understand, prevent, and maybe even treat multiple sclerosis.

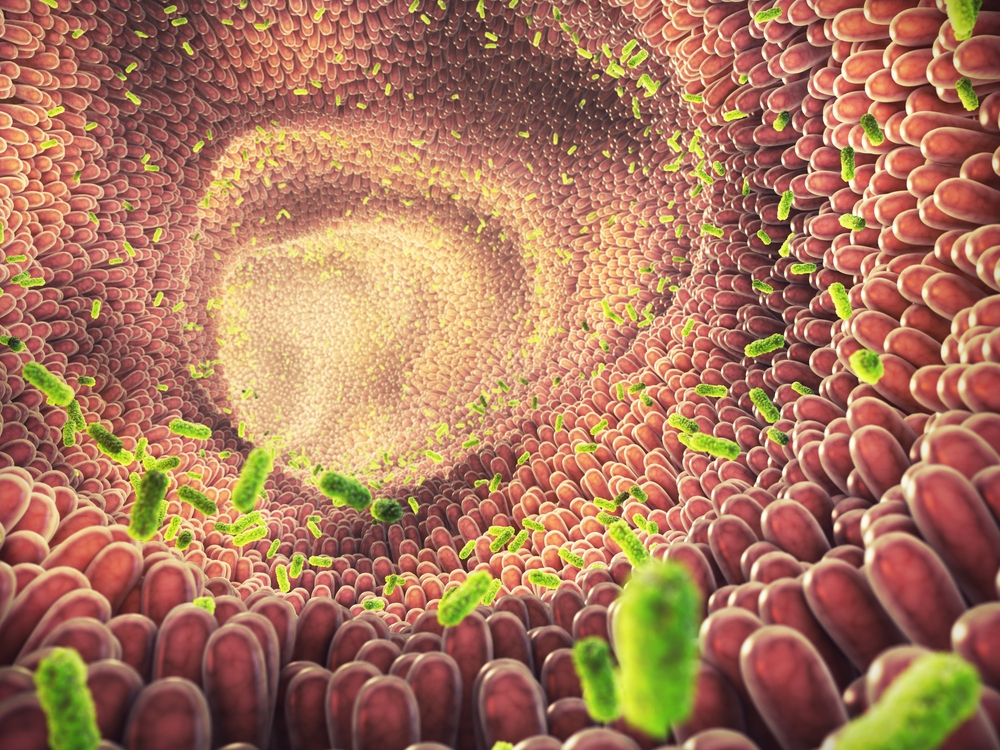

The Role of the Gut Microbiome in MS

The human gut microbiome, the vast community of microorganisms living in our intestines, has long been recognized for its essential role in digestion and overall health. However, recent studies have increasingly shown that these gut microbes do much more than just help us digest food—they also play a critical part in regulating our immune system. A healthy gut microbiome contributes to immune balance, protecting against infections and ensuring the immune system functions properly. But when the balance is disrupted, it can lead to immune system problems and, in some cases, autoimmune diseases.

Multiple sclerosis is one such autoimmune disease where the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. It is widely accepted that genetics and environmental factors influence MS development, but how exactly the immune system becomes dysregulated has remained unclear—until now.

Over the years, scientists have observed changes in the gut microbiomes of MS patients, but previous studies have been inconclusive. Many studies failed to pinpoint specific bacteria linked to MS, and the findings often contradicted each other.

A major breakthrough came with a study that focused on a unique cohort of individuals: monozygotic (identical) twins. By studying twins where one was affected by MS and the other was healthy, researchers were able to rule out genetic and early environmental factors as the primary causes, narrowing their focus to the gut microbiome as a potential trigger for the disease. This twin-study design provided the most accurate picture of how gut bacteria might influence MS development, ultimately revealing a crucial piece of the puzzle.

The Twin Study That Changed Everything

When it comes to medical mysteries like multiple sclerosis, identical twins are a researcher’s dream. Why? Because they share the same genes, similar childhood environments, and even the same brand of cereal growing up. So when one twin develops MS and the other doesn’t, scientists pay attention. Big time.

In one of the most ambitious studies of its kind, researchers followed over 80 pairs of monozygotic (identical) twins—where only one sibling had MS. This clever design stripped away the usual noise of genetic variability and focused purely on environmental and biological differences.

The results were fascinating.

Instead of just looking at the usual suspects like diet or geography, scientists zoomed in on a less obvious but increasingly suspicious player: the gut microbiome. You know, that bustling metropolis of trillions of bacteria living in your digestive tract? It turns out that MS-affected twins had very different microbial communities compared to their healthy siblings. Over 50 bacterial species showed up in different amounts—but two stood out like villains in a whodunit.

Rather than stopping at observation, researchers went a bold step further. They extracted gut bacteria—specifically from the small intestine—of both MS and healthy twins and transferred them into germ-free mice genetically predisposed to develop MS-like symptoms.

The Bacterial Culprits: E. tayi & Lachnoclostridium

If gut bacteria had a Most Wanted list, Eisenbergiella tayi and Lachnoclostridium would now be on it.

When researchers introduced gut microbes from MS-affected twins into germ-free mice, the results were dramatic—especially when those samples came from the ileum, a segment of the small intestine that’s something of a hot zone for immune activity. Several of these mice developed MS-like disease symptoms, while those that received bacteria from the healthy twins stayed in the clear.

Digging deeper, scientists discovered a pattern: in every mouse that got sick, one of two bacterial species dominated the gut environment—E. tayi or Lachnoclostridium, both members of the Lachnospiraceae family.

Here’s where things get even more intriguing. These bacteria weren’t major players in the original human samples—they were low-abundance microbes, quietly lurking in the shadows. But once they entered the mice, they “bloomed” into dominance. And as they grew, so did the neurological inflammation.

Even more telling? These effects weren’t random. Female mice were disproportionately affected—echoing the gender imbalance seen in human MS, where women are two to three times more likely to develop the disease. The sick mice also showed hallmark features of MS-like damage: inflammation, demyelination, and changes in immune cell behavior, including an uptick in the notorious Th17 cells known to be involved in autoimmunity.

From Gut to Brain: How These Bacteria Spark MS

Once E. tayi and Lachnoclostridium settled into the guts of genetically predisposed mice, they didn’t just hang out. They got to work. These bacteria appeared to trigger the activation of Th17 cells, a type of immune cell notorious for its role in autoimmune conditions. Think of Th17s as the overzealous bouncers of the immune world—except in MS, they storm the central nervous system (CNS) and start attacking the protective myelin sheath around nerves.

As these cells move from the gut to the brain and spinal cord, they bring inflammation along with them. The result? Damage to myelin, disrupted neural communication, and symptoms that mimic early-stage MS—right down to muscle weakness and coordination issues.

Here’s what makes this even more remarkable: the damage wasn’t just theoretical. In affected mice, researchers saw visible signs of CNS inflammation, including demyelination and immune cell infiltration—basically, the molecular version of a crime scene.

What’s more, it wasn’t just the immune attackers that made an appearance. Certain “good” bacteria that usually keep gut ecosystems balanced—like Akkermansia and Bacteroides—were pushed out. It was like the bad guys took over the town and shut down the peacekeepers.

This pattern held across multiple experiments and different twin donors. Whether the MS-affected donor was a woman with long-term disease or a man with a mild, early case, the same bacterial troublemakers showed up, and the same neurological chaos followed. The gut-brain axis wasn’t just involved—it was ground zero.

What This Means for MS Prevention and Treatment

For starters, this research shifts the focus from simply managing symptoms to possibly preventing the disease before it starts. Imagine being able to screen someone’s gut microbiome for telltale troublemakers like E. tayi or Lachnoclostridium. If caught early, interventions could be made long before neurological symptoms ever appear.

This could also mean a new wave of personalized medicine. Treatments might no longer rely solely on immune-suppressing drugs—which, let’s be honest, often come with a suitcase of side effects. Instead, we might fine-tune the gut microbiome itself using targeted antibiotics, probiotics, or even fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) to crowd out the harmful bacteria and restore a healthy balance.

And what about diet? Since what we eat directly influences our gut flora, nutrition could play a bigger role in MS care than ever before. A future MS treatment plan might include more than just prescriptions—it could involve customized food regimens designed to starve out the bad bacteria while nourishing the good.

There’s also hope for better treatment matching. If we know a certain patient’s disease is linked to a specific microbial imbalance, their care team could avoid the guesswork and tailor therapies accordingly. It’s not hard to imagine a near future where neurologists and gastroenterologists team up to build dual-pronged MS strategies that start in the gut and end in the brain.

How to Support Your Gut and Potentially Lower MS Risk

While more research is needed to fully understand how gut bacteria specifically trigger MS, maintaining a healthy gut microbiome can have wide-ranging benefits for your overall health and immune function. Here are some practical tips to support a balanced gut environment and potentially lower the risk of MS and other autoimmune conditions:

- Focus on a Fiber-Rich Diet:

A diet rich in prebiotic fibers helps nourish the beneficial bacteria in your gut. These fibers are found in foods like leafy greens, garlic, onions, asparagus, oats, bananas, and legumes. Fiber helps to promote the growth of short-chain fatty acid–producing bacteria, which are linked to reduced inflammation and improved gut health. - Incorporate Fermented Foods:

Fermented foods are natural sources of probiotics, the “good” bacteria that can restore balance to your gut microbiome. Include foods like yogurt with live cultures, kefir, sauerkraut, kimchi, miso, and kombucha in your diet. Start slowly if you’re new to these foods, as your gut may need time to adjust. - Limit Processed Foods and Sugar:

Highly processed foods and refined sugars feed harmful bacteria and yeast, which can disrupt the balance of your gut microbiome. Whole foods with minimal ingredients are generally better for gut health. Reducing your intake of sodas, candy, white bread, packaged snacks, and fast food can help keep your gut in balance. - Exercise Regularly:

Physical activity not only strengthens your muscles and heart, but it also supports a healthy gut microbiome by increasing bacterial diversity and lowering inflammation. Aim for at least 30 minutes of moderate exercise most days—activities like walking, cycling, swimming, or yoga can all be beneficial. - Reduce Smoking and Manage Stress:

Smoking has a known negative impact on the gut microbiome, increasing inflammation and making the immune system more likely to go awry. Quitting smoking can help reduce MS risk and improve your gut health. Additionally, chronic stress can disrupt the gut-brain axis and decrease microbial diversity. Practices like meditation, breathwork, or even a daily walk in nature can help manage stress and support gut health.

These lifestyle changes may not only support your gut but could also be a proactive step in reducing your MS risk. Remember to consult with a healthcare provider before making significant changes to your diet or lifestyle, especially if you have concerns about your health or risk for MS.

A New Frontier in the MS Mystery

For decades, multiple sclerosis has been a condition defined by uncertainty. Now, for the first time, science has traced a clear thread—from the gut to the brain—revealing microbial fingerprints on the roots of MS. It’s a discovery that doesn’t just add another layer to our understanding; it potentially rewrites the narrative.

By identifying specific bacteria—E. tayi and Lachnoclostridium—as agents capable of triggering MS-like disease, researchers have opened the door to earlier detection, more personalized treatment, and even new preventative strategies. While we’re still in the early stages, the implications are massive: MS may no longer be a disease that simply “happens.” It might be one we can predict, modify—or one day, even stop in its tracks.

Until then, the best steps we can take are proactive ones. Nurturing a healthy gut, staying informed, and supporting continued research may be the most powerful tools available today.

The conversation around MS is changing. And this time, it starts in the gut.

Source:

- Yoon, H., Gerdes, L. A., Beigel, F., Sun, Y., Kövilein, J., Wang, J., Kuhlmann, T., Flierl-Hecht, A., Haller, D., Hohlfeld, R., Baranzini, S. E., Wekerle, H., & Peters, A. (2025). Multiple sclerosis and gut microbiota: Lachnospiraceae from the ileum of MS twins trigger MS-like disease in germfree transgenic mice—An unbiased functional study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(18). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2419689122