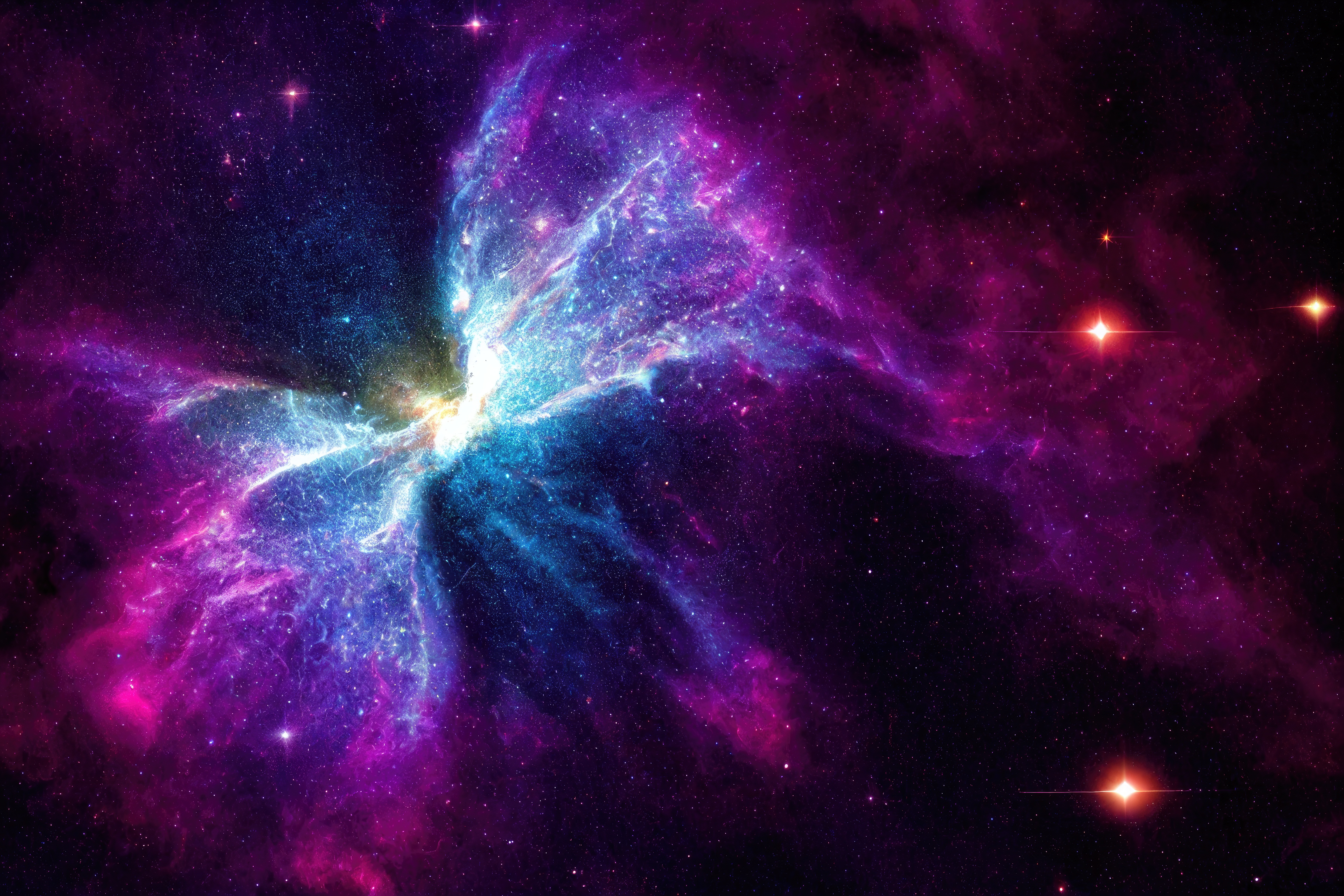

A telescope high in the Chilean Andes just captured a new close-up of something nicknamed the Butterfly Nebula, and it looks like a glowing creature caught mid-flight. The image is more than space eye candy. It’s a snapshot of what can happen when a star reaches the end of its life and pushes its outer layers into space, lighting up the surrounding gas in striking colors.

The “Cosmic Butterfly” and the Star at Its Center

The new image released by the U.S. National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab highlights NGC 6302, a bright, wing-shaped cloud of glowing gas and dust often called the Butterfly Nebula (also known as the Bug Nebula or Caldwell 69). It was captured by the Gemini South telescope on Cerro Pachón in central Chile, one of two 8.1-meter telescopes that make up the International Gemini Observatory.

NGC 6302 is about 2,500 to 3,800 light-years from Earth in the constellation Scorpius. What looks like “wings” is material that a dying star pushed out into space. At the center is a white dwarf, the dense remnant left after a Sun-like star sheds its outer layers. That discarded gas and dust becomes visible because radiation and heat from the central star energize it, making it glow.

This target was selected through an anniversary program tied to the telescope’s history. NOIRLab noted that it was “chosen as a target… by students in Chile as part of the Gemini First Light Anniversary Image Contest.” The contest was designed to engage students in the host regions of the Gemini telescopes as Gemini South marks 25 years since its first light in November 2000.

The image was also produced as part of NOIRLab’s public-facing imaging efforts that dedicate observing time to color data specifically meant to be shared widely, not just analyzed by specialists.

The Life Stage Behind the Butterfly Nebula

NGC 6302 is classified as a planetary nebula, but it has nothing to do with planets. The term came from early telescope observations, when many of these objects looked like small, rounded disks. Astronomers later learned they were not planets at all, but the name remained.

A planetary nebula forms near the end of a star’s life, after it has used up the fuel that keeps it stable. As the star changes, it sheds its outer layers into space. That material spreads outward and becomes a large shell of gas and dust. What makes it visible is the radiation from the hot stellar remnant at the center, which energizes the gas so it glows.

NGC 6302 is an example of how dramatic this phase can look. Instead of a simple round shell, it has two main lobes, which is why it is described as a bipolar planetary nebula. The central star has been identified as a white dwarf, the dense remnant left behind after a Sun-like star loses its outer layers.

This is not just a distant curiosity. Astronomers expect the Sun to go through a similar general end stage, eventually becoming a white dwarf after shedding its outer layers. Some sources estimate that this will happen in about 5 billion years. That makes objects like NGC 6302 useful for explaining what “stellar aging” can look like, even if the details will differ from star to star.

How NGC 6302 Got Its Butterfly Shape

The Butterfly Nebula looks dramatic because the gas did not expand evenly in all directions.

Before the central star became a white dwarf, it went through a red giant phase. During that stage, it shed large amounts of gas and dust. Studies described a dense, dark band around the star, often compared to a donut shape. Material moving outward along the star’s equator appears to have formed this thick belt. That belt then acted like a barrier, narrowing and guiding later outflows.

Instead of producing a more typical round planetary nebula, additional gas was pushed out in two main directions, roughly perpendicular to that central band. That is what creates the two-lobed, bipolar structure that looks like wings.

Later, as the star evolved into a white dwarf, it produced faster winds that tore through earlier, slower-moving material. NOIRLab reports wind speeds exceeding three million kilometers per hour. The push and pull between slower gas and faster winds helps explain the textured look seen in detailed images, including ridges, pillars, and layered edges.

The central white dwarf is also extreme in temperature. NOIRLab notes its surface temperature is above 250,000 degrees Celsius, and the energized gas in the nebula can reach over 20,000 degrees Celsius. That heat and radiation are what make the nebula shine so brightly in telescope images.

The Elements a Dying Star Sends Back Into Space

The colors in the Gemini South image are a guide to the chemistry in the nebula.

According to NOIRLab, the red highlights regions dominated by energized hydrogen gas, and the blue highlights regions dominated by energized oxygen gas. Telescopes can isolate specific wavelengths of light tied to these gases, then combine them into a color image so the structure and composition are easier to see.

NOIRLab also notes that scientists have identified other elements in NGC 6302, including nitrogen, sulfur, and iron. That matters because planetary nebulae are one way stars return chemically enriched material to the space between stars.

Over long timescales, that dispersed material can mix into new clouds of gas and dust that later form stars and planetary systems. NGC 6302 is a clear example of that handoff: the star’s outer layers are no longer part of the star, but they are still part of the galaxy’s building material.

This image was created through NOIRLab’s public imaging efforts that dedicate observing time to produce color data for outreach, not just for technical analysis.

Let Curiosity Be the Point

NGC 6302 is a reminder that big change is not rare, even in nature. This “cosmic butterfly” is what it looks like when a star reaches the end of one phase and sheds what it no longer needs. That material does not disappear. It becomes part of what comes next.

Make it personal in a simple way. The next time a space image stops the scroll, do one small thing with it: read the caption, look up one term, or find where the object sits in the sky with a stargazing app. If there’s a kid nearby, show them and ask, “What do you think this is?” Curiosity grows faster when it’s shared.

And remember why this image exists at all. NOIRLab said the Butterfly Nebula was “chosen as a target… by students in Chile as part of the Gemini First Light Anniversary Image Contest.” That is the point. Science is not only for experts. It’s for people who ask questions, follow the evidence, and stay open to learning.